For many of our new members, all the Japanese terms used in class can be confusing. From my own experience I know it’s taken me months to get to know most of the common terms. Of course students can find help in the glossary compiled by our teachers, but at times a bit of extra explanation may be helpful.

We continue our series of explanatory articles with commands from the line-up. We will also provide an explanation of dojo layout.

As noisy and violent kendo class may be, there are two moments that form a stark contrast: at the beginning and end of class all students line up to thank their classmates and teachers and to meditate. The dojo is plunged into quiet, while students prepare their armor and ready themselves. Usually it’s the highest ranking student (not the sensei themselves) who call out the following commands.

- Seiretsu (整列) Literally, “form a line“. While the sensei are seated on their side of the room, the students line up according to their rank (see explanation about dojo layout). Everyone holds their shinai in their left hand, hanging gently downwards. Those who have armor, wear their tare and dou, while holding their men under their right arm (with kote and tenugui inside the helmet). In our case, the lowest ranking students sit on the left and the highest ranking students at the right. Visitors will always be on the right-hand side of their rank group. Sometimes we change the order a little bit, by lining up based on age.

- Seiza (静坐) There are two distinct and applicable ways of writing “seiza“: 静坐 “to sit peacefully“, or 正座 “to sit kneeling“. If you are not yet sure how to properly sit down into seiza, Kendo World made a great video about seiza. When seated, the kendoka place their shinai on the floor (lying on the tsuru). Those with men take the kote from the men and place them on the floor. The men is then balanced on top, with the tenugui draped over it neatly.

- Shisei wo tadashite (姿勢を正して) Literally, “straighten yourselves“. While seated, you are to sit upright and with a straight back. Do not slouch, do not fiddle with your uniform, just pay attention and sit up straight.

- Ki wo tsuke (気を付け) A call to “stand to attention“, similar to “shisei wo tadashite“. Again, it means you should focus and pay close attention to the proceedings.

- Mokuso (黙想) The word mokuso refers to meditation in general. While there are many kinds of meditation, in our case we know two kinds: EITHER try to empty your mind completely (mushin), OR focus your thoughts on today’s lesson or on specific points of improvement. Don’t close your eyes completely, cup your hands in your lap and think about what you need to learn. For more details on mokuso, watch this great Kendo World clip.

- Mokuso yame (黙想辞め) As in all commands issued in class, yame means “to stop”. It is the call to stop meditation, to bring your attention back to class and to be prepared.

- Rei (礼) Literally means “to express gratitude“, so while the word rei is used as a command to bow it is actually a request to show thanks.

- Shomen ni rei (正面に礼) Not used in our dojo, but included for completion’s sake. “Bow to the front“, which includes the “highest” seat in the room (see below). One could say that you are bowing to the dojo itself and to the spirit of budo, to thank for the lessons learned and the protection provided inside the dojo. You also bow to shomen when entering and leaving the dojo.

- Shinzen ni rei (神前に礼) Not used in our dojo, but included for completion’s sake. A call to “bow to the altar“, which is usually only used if the dojo has a kamidana (see below) and if the dojo is non-secular. One bows to thank the ancestors, sensei from the past and possibly a deity.

- Sensei ni rei (先生に礼) Literally “thank your teacher“.

- Sensei gata ni rei (先生方に礼) Literally “thank your teachers“, with “gata” being the honorific for a group of people.

- Otagai ni rei (御互いに礼) Literally “thank each other“. You thank your classmates for practicing together and for learning from each other.

- Sougo ni rei (相互に礼) Literally “Show mutual thanks”, quite the same as the previous command.

- Men wo tsuke (面を着け) “Put on your mask“, the command to don your tenugui, helmet and gloves.

- Men wo tore (面を取れ) “Remove your masks“, the command to take off your protection (except dou and tare). In September Heeren-sensei explained how to properly take off your helmet, showing enough respect (at the bottom of this summary).

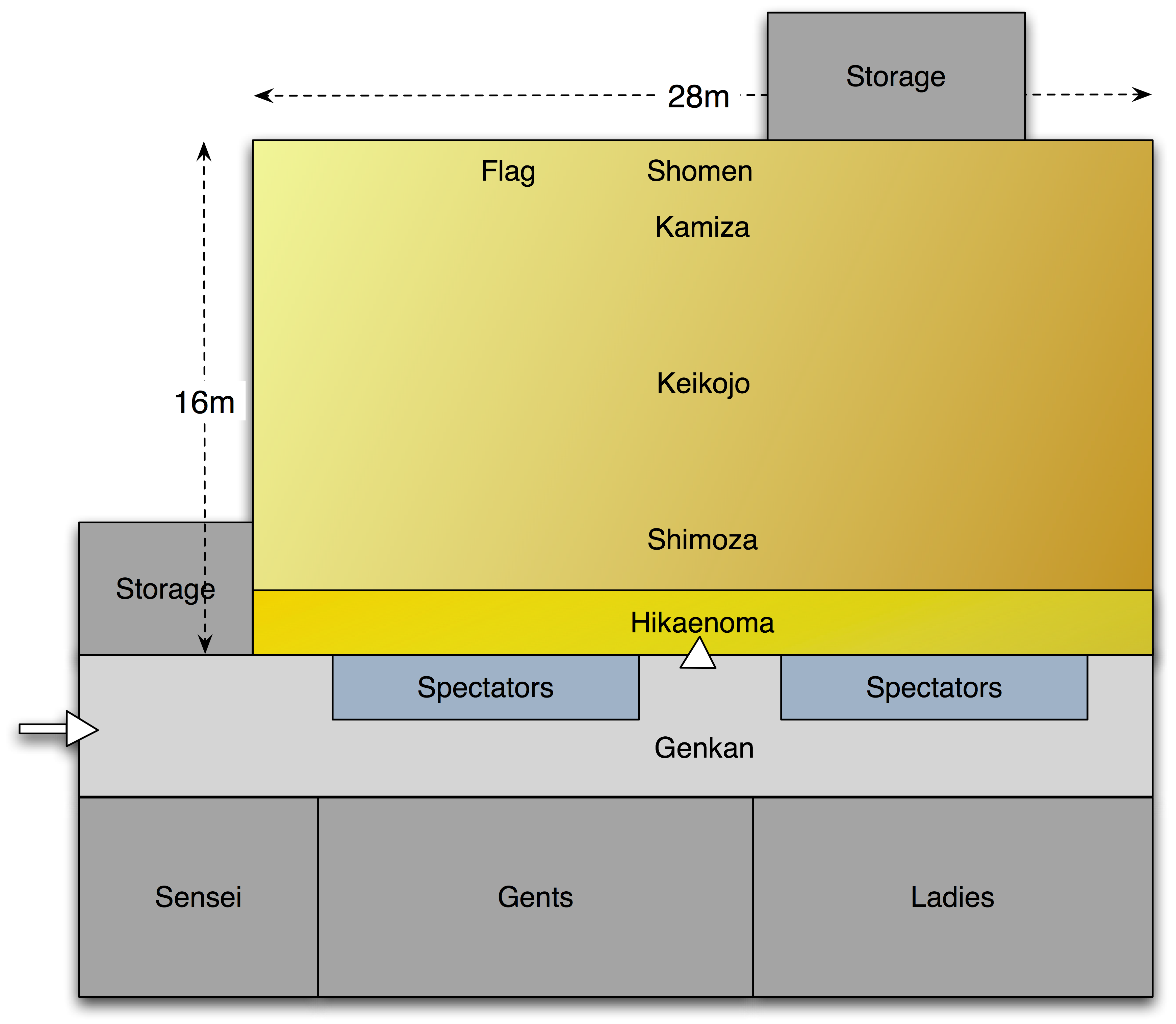

The preceding paragraphs have already mentioned a lot of terms describing parts of the dojo. Below is a drawing of the Amstelveen dojo, with the most important terms shown in the right location. Both the drawing and the lexicon below could only have been made because of Dillon Lin’s excellent article on dojo layout.

- Genkan (玄関) The entrance foyer, leading to the dressing rooms. Officially the term genkan is reserved for a foyer where one takes off ones shoes, but apparently it’s not incorrect to apply it to the tiled section of the gymnasium we train in.

- Hikaenoma (控えの間) The perimeter of the dojo nearest to the entrance is used as temporary storage space. Shinai are put down here when not used and the kendoka place their men and kote here before class. Kendoka who need to quickly drop out from an exercise (for example to fix their armor) will also sit down in the hikaenoma.

- Shimoza (下座) Consisting of the kanji for “bottom” and “sit”, this is the junior side of the dojo. All students line up here, according to their rank.

- Shimoseki (下関) This is literally the lowest seat in the dojo, at the far left of the shimoza.

- Keikojo, or embujo (稽古場, or 演武場) Literally, “training place“. The center of the dojo is used for training.

- Kamiza (上座) Consisting of the kanji for “top” and “sit”, this is the senior side of the dojo. The teachers in charge of class will sit on this side.

- Joseki (上席) The “highest seat” in the room, which you could say is the VIP seat. In our case, this is on the right-hand side of the kamiza (in the picture that is). This seating is reserved for visiting sensei, high-placed visitors and officials, who are to observe class.

- Shomen (正面) The “front” of the dojo, the wall along which the kamiza is aligned. We bow towards shomen when entering and leaving the dojo.

- Kamidana (神棚) In Japan’s religion Shinto, the kamidana is a small shrine or altar kept inside the household, office, dojo or various other places. A kamidana consists of many objects, all of which are very well described by the aforementioned Dillon Lin in this article about budojo no kamidana.

- Tokonoma (床の間) In Japan many rooms have a niche in the wall, containing a piece of calligraphy, a work of art or an ikebana arrangement.

Our Amstelveen dojo may have neither of these two, but one could argue that the flag replaces the kamidana. Our flag is there to remind us of the dojo motto and to act as a reminder of the required frame of mind.

As always, I would like to thank Zicarlo for reviewing this article.

Voor veel nieuwe kendoka kunnen al die Japanese termen maar verwarrend zijn. Uit eigen ervaring weet ik dat het maanden kan duren voor je de meest gebruikelijke termen correct kent. Natuurlijk is de woordenlijst die onze leraren hebben opgesteld erg handig, maar soms is wat extra uitleg handig.

We vervolgen deze serie artikelen met de commando’s die je hoort tijdens het opstellen in de rij. En we verklaren termen die horen bij de layout van de dojo.

Kendo is een luidruchtige en wat gewelddadige sport, maar er zijn twee momenten in een les die een enorm contrast vormen met de rest van de dag: aan het begin en het einde van de training vormen alle leerlingen een rij om hun klasgenoten en hun leraren te bedanken en om te mediteren. De dojo valt in een diepe stilte en de studenten bereiden zichzelf en hun pantsers voor op de les. Het is doorgaans de hoogstgeplaatste leerling die de volgende commando’s afroept.

- Seiretsu (整列) Letterlijk, “vorm een rij“. Terwijl de sensei aan hun kant van de zaal zitten stellen de studenten zich op in volgorde van hun rank. Iedereen heeft zijn shinai in de linker hand. Zij die een harnas dragen hebben de tare en dou aan, terwijl ze hun men (met de kote en tenugui er in) onder de rechterarm dragen. In ons geval zitten de laagste studenten links en de hoogst gegradeerde studenten rechts. Bezoekers staan binnen het groepje van hun rang, altijd rechts. Soms houden we een andere opstelling, gebaseerd op leeftijd, aan.

- Seiza (静坐) Er zijn twee manieren om “seiza” te schrijven: 静坐 “kalm zitten“, of 正座 “knielend zitten“. Als je niet zeker weet hoe je in seiza moet zitten, dan heeft Kendo World een filmpje gemaakt met uitleg over seiza. Eenmaal gezeten plaatsen de kendoka hun shinai op de vloer (liggend op de tsuru). Zij met een men leggen de kote op de grond en de men balanceert er bovenop. De tenugui wordt over de men heen uitgevouwen.

- Shisei wo tadashite (姿勢を正して) Letterlijk, “straighten yourselves“. Je gaat rechtop zitten met een rechte rug. Zak niet ik, rommel niet met je uniform, let gewoon op en zit netjes.

- Ki wo tsuke (気を付け) Vergelijkbaar met “shisei wo tadashite“. Nogmaals, het betekent dat je op moet letten, dat je moet focussen.

- Mokuso (黙想) Het woord mokuso slaat op meditatie in het algemeen. Er zijn veel vormen van meditatie, maar wij kennen twee mogelijkheden: OF je probeert je geest zo leeg mogelijk te maken (mushin), OF je focust je gedachtes op de les van vandaag en op specifieke punten die we moeten verbeteren. Onze handen liggen vormen een kommetje boven onze schoot en we sluiten de ogen deels. Kijk voor meer informatie over mokuso deze uitstekende video van Kendo World.

- Mokuso yame (黙想辞め) Zoals met alle yame opdrachten betekent het ook hier “stoppen”. We houden op met mediteren en keren onze aandacht weer terug naar de les.

- Rei (礼) Betekent letterlijk “het tonen van dankbaarheid“. Hoewel we het gebruiken als opdracht om te buigen, is het dus eigenlijk een opdracht om te danken.

- Shomen ni rei (正面に礼) Gebruiken we niet in onze dojo, maar staat hier voor de volledigheid. “Buig naar de voorkant”, de “hoogste” zetel van de dojo (zie onder). Men zou kunnen zeggen dat we buigen naar de dojo zelf en naar de geest van budo, om te danken voor de lessen die we leren en voor de veiligheid die we in de dojo genieten. Bij het betreden en verlaten van de dojo buig je ook naar shomen.

- Shinzen ni rei (神前に礼) Gebruiken we niet in onze dojo, maar staat hier voor de volledigheid. Dit is een roep om te buigen naar het altaar, wat je eigenlijk alleen hoort in dojo met een kamidana (zie onder) met een religieuze inslag. Je dankt de voorouders, sensei uit het verleden en mogelijk een god.

- Sensei ni rei (先生に礼) Letterlijk “bedank je leraar“.

- Sensei gata ni rei (先生方に礼) Letterlijk “bedank je leraren“, waar “gata” de eerbiedige term is voor een groep mensen.

- Otagai ni rei (御互いに礼) Lettelrijk “bedank elkander“. Je bedankt je klasgenoten voor het samen oefenen en voor wat je van elkaar hebt geleerd.

- Sougo ni rei (相互に礼) Letterlijk “Toon wederzijdse dankbaarheid“, eigenlijk het zelfde als het vorige commando.

- Men wo tsuke (面を着け) “Zet je masker op“, de opdracht om je tenugui, helm en handschoenen aan te doen.

- Men wo tore (面を取れ) “Zet je masker af“, de opdracht om helm, handschoenen en hoofddoek af te zetten. In September heeft Heeren-sensei uitgelegd hoe je op beleefde wijze je men afzet (onderaan deze samenvatting).

De voorgaande paragrafen noemden al een aantal termen die te maken hebben met het interieur van de dojo. Hier onder zie je een tekening van de Amstelveense dojo, met de belangrijkste termen op de juiste plaats. Zowel de tekening als dit artikel zouden onmogelijk zijn gweest zonder Dillon Lin’s fantastische artikel over dojo layout.

- Genkan (玄関) De entree, de foyer, die leidt naar de kleedkamers. Officieel is de term genkan bedoeld voor de ruimte waar je je schoenen uitdoet, maar schijnbaar is het gebruik in onze gymzaal niet incorrect.

- Hikaenoma (控えの間) De rand rondom de dojo die het dichtste bij de entree is wordt gebruikt als opslagruimte. Shinai worden hier neer gelegd en de kendoka plaatsen hier hun pantser voordat de les begint. Kendoka die kort uit de les moeten stappen zitten ook in de hikaenoma.

- Shimoza (下座) Dit woord bestaat uit de kanji voor “bodem” en “zitten”. De studenten zitten of staan aan deze kant van de zaal, opgesteld naar rang.

- Shimoseki (下関) Letterlijk de “laagste zetel” van de zaal, helemaal links.

- Keikojo, of embujo (稽古場, of 演武場) Lettelrijk, “training plaats“. Het midden van de zaal wordt gebruikt voor training.

- Kamiza (上座) Bestaat uit de kanji voor “top” en “sit”, dit is de senior zijde van de dojo. De leraren die de les leiden zitten aan deze kant.

- Joseki (上席) De “hoogste zetel” van de zaal, je zou kunnen zeggen dat ze voor VIPs is. In ons geval is het de rechter kant van de kamiza (gezien vanuit de shimoza). Deze plaats is bedoeld voor bezoekende sensei en hooggeplaatste bezoekers die de les komen observeren.

- Shomen (正面) De “voorzijde” van de dojo, de muur achter de kamiza. Bij het betreden en verlaten van de dojo buigen we naar shomen.

- Kamidana (神棚) In Japan is de religie Shinto gemeengoed en veel huizen, kantoren en dojo hebben een klein altaar. Een kamidana bestaat uit een aantal objecten die uitvoerig worden beschreven in Dillon Lin’s artikel over budojo no kamidana.

- Tokonoma (床の間) In Japan hebben veel kamers een nis in de mur waar een stuk kalligrafie, een kunstwerk of een ikebana stuk staat.

Onze Amstelveense dojo heeft geen van beiden, maar je zou kunnen zeggen dat onze vlag de kamidana voorstelt. Onze vlag herinnert ons aan het motto van onze dojo en maakt van een gewone gymzaal een dojo.

Zoals altijd bedank ik Zicarlo voor zijn review van dit artikel.